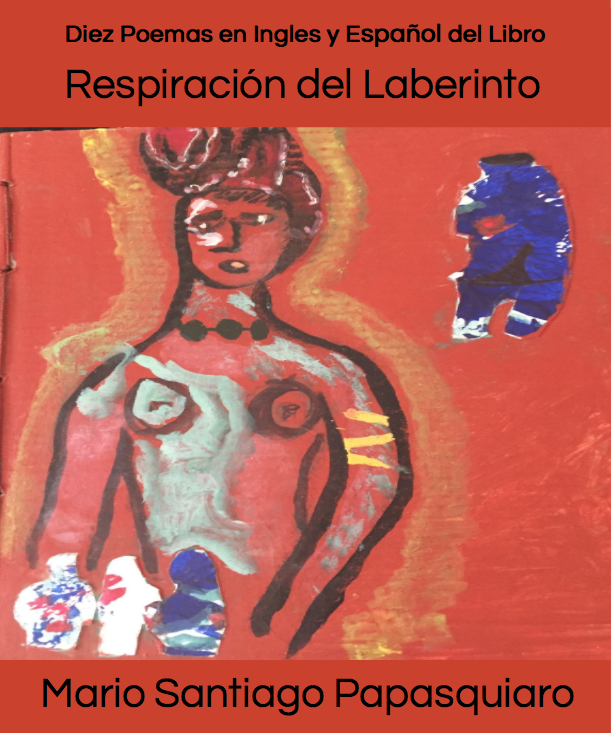

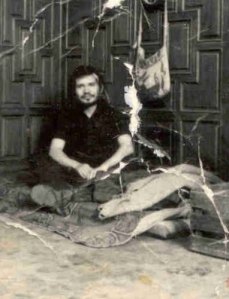

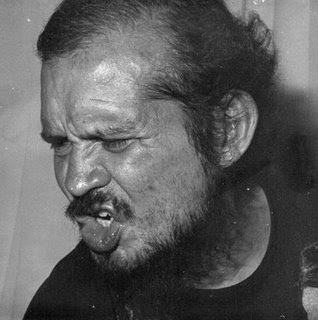

Mario Santiago Papasquiaro, Infrarealist

Commune Editions has released a new collection of Mario Santiago’s poetry, Beauty is Our Spiritual Guernica, which you can download for free here. As I’ve written previously, Santiago was the leading voice of the Infrarealist movement that emerged from Mexico City in the 1970s. The poems within are a fitting testament to the bombastic, establishment-scorning artist and his acidic wordplay. Over email, translator Cole Heinowitz answered some questions about these powerful poems and the process of rendering them in English.

Cole Heinowitz, translator of Beauty Is Our Spiritual Guernica and other works by Santiago.

Paul Murufas: Tell me a little bit about yourself and your history as a translator.

Cole Heinowitz: Raised in an English-speaking household in a predominantly Mexican neighborhood, and attending a grammar school where instruction was in Spanish and English, I grew up bilingual. I came to poetry in the early 1990s when the San Diego-Tijuana border was a kind of cauldron of art, punk rock, and radical activism. NAFTA was passed the year my first book of poetry came out. One of my roommates at the time built radios for the EZLN. Another was jailed for midwifery. We painted a mural of Subcomandante Marcos on the front of the co-op we ran. I studied writing at UCSD when Kathy Acker, Eileen Myles, and Carla Harryman taught there. One year, we staged Carla’s Memory Play in Jerry Rothenberg’s studio (Jerry stole the show as the corpse). The door was open and David Antin kept walking by and peering in. I can’t remember Rae Armantrout’s character, but I think she was there. Those are my beginnings as a translator.

PM: When did you first become interested in translating Santiago?

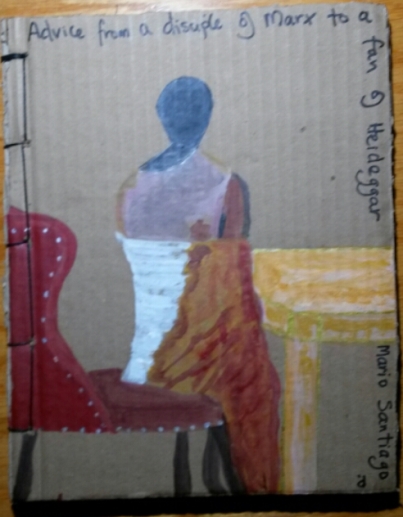

CH: I’ve been teaching literature at Bard College for the last 12 years. Five years ago or so, Alexis Graman, a wonderful painter who was in one of my seminars, asked to do a tutorial on Mario Santiago Papasquiaro (aka Ulises Lima, from Roberto Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives). Through Juan Villoro, I made contact with Mowgli Zendejas, Santiago’s son, in Mexico City. He had just returned from studying Buddhism in Japan and was setting up the first free-form radio station in DF. Jeta de Santo, the beautiful posthumous collection of Santiago’s work, had just been published by the Fondo de Cultura Económica. I think Alexis and I managed to buy the last of the original print run. The major bookstores in DF don’t carry it—but they say it’s in stock so Spain doesn’t send them more copies. Alexis and I read and reread it and decided to translate the 1975 poem Santiago launched like a missile on the Mexican literary establishment, Advice from 1 disciple of Marx to 1 Heidegger fanatic. It took us a year to translate. It’s insane.

PM: How did you link up with Commune Editions?

CH: I met Juliana [Spahr] 15 years ago at a party in her backyard, back when she as living in Brooklyn. Five years later, we were on the Poetry Bus together in northern California. Then last year she got in touch to say she’d loved reading Advice and asked if I had other unpublished translations of Santiago’s work—especially any pieces where his politics were in the foreground.

PM: How did you select the various poems and works that make up Beauty Is Our Spiritual Guernica? How did you select the title?

I picked the pieces where Santiago’s engagement with revolutionary politics is the most vivid and direct. The folks at Commune took the title from the poem “Dismirror.” That poem says a lot about Santiago’s radicalism.

PM: The poems seem to reflect an earlier period than the other Santiago poems I’ve read. What are the dates on these poems? How old would Santiago have been when he wrote these?

CH: Santiago was born in 1953 and Advice was his first published poem. He wrote consistently from 1975 to the year of his death in 1998, but no mainstream publisher wanted to touch him. He released two of his own books through his own imprint, East of Eden—one in 1995 and one in 1996. After Santiago’s death, when his widow Rebeca López and his friend Mario Raúl Guzmán went through his manuscripts to make the selections for Jeta de Santo, they chose 161 poems out of more than 1,500. Who knows how many more are scrawled in the margins of books Santiago borrowed or stole, on bar coasters, magazine covers, and paper bags. Many are probably in a landfill somewhere in the Sonora Desert. To date his poems with accuracy, you have to trace publication dates in obscure literary magazines, study the different color pens he used, or know former Infrarealists. Basically, the pieces in Beauty were written between 1976 and 1996.

The 1968 Tlatelolco Massacre was a vital influence on Santiago and the Infrarealists.

PM: What are your favorite pieces in the collection?

CH: That’s hard since the pieces in that collection are all among my favorites. I love the prose piece, “Second-Hand Heroes: Six Young Mexican Infrarealists”—a seething account of coming of age in Mexico City during the Tlatelolco Massacre:

In 1968: less than 15 years old / watching gringo shows on T.V. / soldiers in the streets / flesh and blood communists agitating everywhere. Onward from there: living experience, living nightmare, living utopia / Emotion, sensation, the certainty of diving into chasms every moment transforming / Radical vagabonds, fugitives from the bourgeois university (the mediocrity of teaching is the teaching of mediocrity)… You can smell the hot days coming, full of blood / There’s a revolution going on in our skins.

Phrases from other poems (“the gunned-down laughter of the dead;” “To hell with Marx / he’s washed in the piss of Utopia”) are permanently etched in my brain. But I guess my favorite pieces are the ones where critique, defiance, and humor emerge alongside an unexpected, almost clumsy, tenderness:

What heroic act

what keatonesque face

will be left us

except the 1 where we catalelepticoluciferianistically

position ourselves like corpses

on the salt-back of 1 imaginary railroad

& there / from that position / from that enclosure

walk our least gnarled paw

across the least melted spotlight of our eyes

until we can’t tell the hairs on our head from the hair on our balls

the eruptions of Mount Venus

from the lava of the Vigilant Mind

While we sing on empty stomachs

1 euphoric thick hot cacao of a tune: There’s no future

(from “Did you notice how the Seine doesn’t look us in the eye anymore & how they filled the Gare de Lyon with propaganda offering $$ for the capture of the Baader Meinhoff Group?”)

PM: Infrarealism might have sunk into obscurity without Bolaño’s runaway fame train after his death. Is there an opening today for a new Infrarealism, or a permutation of it?

CH: “I kill what I speak / :: Swan’s howl ::” That’s the last couplet of the poem “Swan’s Howl.” No, I don’t think there’s an opening today for a new Infrarealism, anymore than there’s an opening for a new surrealism. Infrarealism was born in an ecstasy of extinction. Nowadays, most writers who were working in Mexico during the 1970s and 1980s either memorialize it or dismiss it. On the other hand, Infrarealism doesn’t need a new opening—it’s already living inside us. As Santiago put it in “Ecce Homo,” “There’s no larva that hasn’t caught my virus.”

PM: Talk a little bit about these very visceral, passionate poems in Beauty. Santiago’s ability to supercharge language is something really rare in poetry today (at least for me). How was that for translating? And for reading in the original?

CH: In the original Spanish, the first thing that comes through is the poems’ incredible velocity—both in their colloquial speech rhythms and in their rapid-fire images. Their physical force bursts through every channel. No matter how you translate the poems, that power inevitably comes through. The cultural and historical specificity of Santiago’s language—from his 1970s street-speak to his use of Nahuatl words—is the biggest challenge. I couldn’t have known, for example, that ornitorrinca used to be a way to describe an inexplicably attractive woman with a savage, almost ugly look. The word doesn’t exist in any Spanish dictionary—ornitorrinco means platypus, but it always has a masculine ending. Tlachiquero (the person who extracts the juice of the maguey from which pulque is made)—that was another impossible one to bring over into English. But these are words that most Spanish speakers wouldn’t know either…

PM: Do you have any translation work or creative writing that you’re working on now?

CH: I’m working on a collected Santiago, which is an oxymoron because so much of what he wrote has disappeared. So it’s really not a collected, but the biggest selected works I can make out of what he published during his lifetime and the papers he left behind. I’m also working on a new play and a collection of poems addressed to people I have known in some way, both living and dead.